Every business leader who must assess a company’s financial performance and make decisions should know how to read a profit and loss statement. Yet, as a fractional Chief Financial Officer (CFO) who works closely with leadership teams, I have noticed that many do not receive this training. Although I’m happy to educate clients on the basics, everyone could benefit from this knowledge. So, below, I explain the purpose of the profit and loss (P&L) report, its essential components, and how to analyze a P&L statement to unearth valuable insights.

What is a Profit and Loss Statement?

A profit and loss statement (a.k.a. P&L statement or income statement) is a financial document showing how your organization generated and spent money to produce a profit (or loss) over a specific period of time. Put differently, the P&L explains how your revenue and expenses contributed to your company’s financial health.

Profit and loss statements are one of three core financial reports business leaders use to monitor a company’s economic performance. The other two financial statements are the balance sheet (a tally of assets and liabilities at a specific point in time) and the cash flow statement (a report of how cash has moved in and out of the business over time).

Ideally, your team will produce and review these reports regularly – monthly, quarterly, and yearly.

The No-BS Financial Playbook for Small Business CEOs

Are you tired of making costly financial mistakes? Stop guessing and start growing. Learn how to create a scalable and valuable company while minimizing risk with this playbook from a serial entrepreneur who has been in your shoes.

What is the Purpose of a P&L Report?

To run a financially viable business and make informed decisions, you must know:

- How much money is coming into the business (your income)

- How much money is going out (in the form of the cost of revenue and operating expenses)

- How this activity affects your bottom line

That is the primary purpose of a profit and loss statement. If the data behind the report is sound and meets accounting conventions, you can assume you are profitable if you generate more money than you spend. If the inverse is true, you are running the business at a loss.

However, that is only part of the story. The magic happens when you and your leadership team set goals and then use the data in your P&L statements (and other reports) to track trends and forecast the future. That gives you the insights you need to strategically guide your growing organization, spotting and addressing problems before they spin out of control.

Profit and loss statements are also necessary for communicating with stakeholders. For example, when you file your taxes, the IRS will expect an abridged copy of this report. Lenders, investors, and significant customers will also ask for this information.

Of course, no one expects you to prepare these reports alone. Most CEOs hire a Chief Financial Officer (CFO) or a fractional CFO to own this business function. The CFO ensures the numbers behind the reports are accurate and then analyzes them to develop insights and recommendations. That said, understanding the basics will make these discussions more productive.

How to Read a P&L Statement Step-by-Step

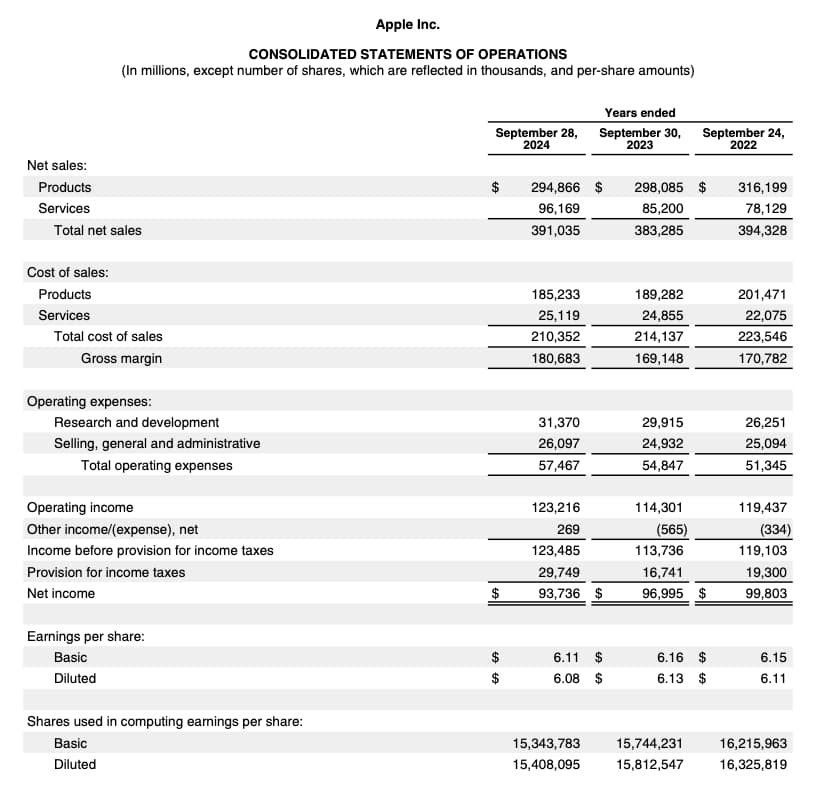

Profit and loss statements present financial information logically, organized into components with subtotals. Here is the basic flow.

- Revenues

- Costs of Revenues

- Gross Profit (revenues minus cost of revenues)

- Operating Expenses

- Operating Income (gross profit minus operating expenses)

- Other Income and Expenses

- Net Income (operating income minus other expenses)

Your P&L may look slightly different, depending on your industry and the maturity of your accounting function. For instance, if you run a small business with little accounting oversight, your expenses might appear under just one of these areas—a situation I suggest remedying for better insights. Also, consider the following tips before reviewing the numbers on a P&L.

Tip 1: Financial Notes

Reading a profit and loss statement without context is challenging. If you are looking at a P&L for a company you don’t know, review any notes included with the report or consider obtaining additional information from a company like Dun & Bradstreet. For instance, the notes might explain certain events or the company’s accounting practices, which will help you understand the nuances.

Tip 2: Accrual vs. Cash-Based Accounting

It is crucial to know whether the company uses accrual or cash-based accounting. Accrual-based accounting is when you recognize (record) revenue and the associated expenses when earned or incurred (i.e., when the product or service is delivered, or you incur a cost). That differs from cash-based accounting, where you recognize (record) revenues and expenses when you receive or distribute cash. Although this distinction may seem minor, and many small companies can get along just fine with cash-based accounting for a while, it is incredibly impactful for the following reasons.

- Accrual-based accounting allows you to monitor revenues and expenses resulting from the same activity in the same time period. That makes it possible to compare apples to apples and glean better insights.

- Lenders and investors typically request accrual-based records, not cash-based records, for better visibility into your company’s financial health.

For these reasons, we typically recommend that our cash-based clients switch to accrual-based accounting as soon as possible.

With that in mind, here’s what you will find in each section of the P&L report.

Revenues

We typically divide total revenue (sales) data into multiple line items, one for each source. For example, companies selling products and services should separate their sales figures into two high-level “product” and “service” buckets, then break them down further into individual product lines and service types for analysis and benchmarking.

Cost of Revenues

After revenues, is “cost of revenues” (a.k.a. cost of sales) or “cost of goods sold” (COGS). These are expenses directly related to delivering your services or producing your products. Service-based costs include employee salaries and related benefits for those directly servicing customers (“the fee earners”), subcontractor costs, client-related travel, etc. Product-based costs include the raw materials, labor, etc., related to making products.

Operating Expenses

Operating expenses are the day-to-day operational costs necessary for your business to function that are not directly related to producing your products or services. Sometimes referred to as “OpEx” or Overheads, this category includes sales and marketing costs, owner compensation, and general and administrative expenses like rent, insurance, and payroll.

Like revenues, carefully tracking and categorizing these expenses is essential for valuable insights. You can use this information to manage your budget, track the ROI on specific investments, benchmark against other firms, and share details with external stakeholders.

Other Income and Expenses

Expenses or income not falling into the two categories above will appear here. This section can contain many different types of costs or revenues that may not be recurring, so again, categorization is vital. For instance, profit from selling equipment, interest expenses, bad debt, income tax, or “special project” costs will fall under other income and expenses.

Net Income

Of course, you will find net income at the bottom of the P&L report; this is the profit or loss after subtracting the total expenses. To arrive at your net profit margin, divide net income by your total sales.

What is EBITDA?

Some companies also show EBITDA on their P&L statements. EBITDA (Earnings Before Interest, Tax, Depreciation, and Amortization) is a commonly used measure of business performance. It is essential because it provides a clear picture of operational profitability across companies with different capital structures and tax rates.

EBITDA also helps to establish a company’s valuation, which is why you will hear that the company sold for 4x or 5x EBITDA. However, Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) does not define this figure, so its composition can vary from industry to industry.

There are several ways to measure company profitability, not just EBITDA, so it is vital to understand the nuances of whichever figure you choose to view or quote.

Given this context, please review the example profit and loss statement below to confirm your understanding before pressing forward.

How to Analyze a Profit and Loss Statement

Once you understand the components of a P&L and how they come together to present the whole picture, it becomes easier to perform an analysis. You can look at this data in two ways – vertically or horizontally.

A vertical analysis involves showing each cost line as a percentage of the company’s revenue and then examining the figures from top to bottom to see how they relate to each other and industry benchmarks. A horizontal profit and loss statement analysis examines how each figure (including the percentages) changes over time (i.e., the trends) and how that might evolve if your trajectory continues.

To perform a good analysis, you must look at the numbers both ways, asking questions like the following for each area.

- Given my perspective, what do these numbers mean for me? In other words, I typically review P&Ls from a business owner’s perspective. CEOs want to know if the company will reach its goals, where efficiency opportunities lie, and whether they can afford specific initiatives. However, if you are a prospective investor, lender, or customer considering doing business with the company, you will examine the P&L differently.

- Is the figure in question above or below industry norms?

- Is the figure increasing or decreasing over time?

- If this figure differs from what you expected, given the company’s goals, industry norms, or other comparisons, can you determine why?

- How might the company resolve the situation? For example, if costs are too high, it could charge more, implement cost-cutting measures, or both.

Let’s dig into key figures to show you what I mean.

Revenue

Ideally, a company’s revenue numbers will show a smooth upward trajectory over time, not significant swings up and down. That indicates that the company is growing in a controlled and predictable fashion. However, we don’t live in a perfect world, and there will be differences depending on the industry, growth stage, business activities, etc. Therefore, you must dig into the details.

For example, where are any changes in these numbers coming from, and how have those changes evolved? They may stem from a specific region, product line, business unit, or customer segment. If one area grew as a percentage of overall revenues while another shrank, that can help you pinpoint opportunities and threats.

You can also look vertically at the company’s balance sheet or cash flow statement for clues. If a positive change occurred, was it the result of a product launch, an investment in marketing, or something else?

Gross Profit Margin (Gross Profit / Revenue = X%)

Gross margin is essential because it helps you see how much money the firm makes as a direct result of selling its products and services after subtracting the cost of revenue or COGS but before other expenses. In other words, this is an efficiency measure you can track over time to answer most of the questions above.

However, once again, you must look behind the figures on the page. For instance, if you are reading the profit and loss statement for a retail or manufacturing company, how do they value the inventory that appears in their cost figures (FIFO or weighted average)? Or, if you are looking at a service-based firm, what do they charge for an hour of labor? What are their “billable” vs. “non-billable” hours? No one can bill for all their time, so reviewing this information can help you understand what is happening.

Operating Margin (Operating Income / Revenue = X%)

The operating margin ratio looks at how much the company has made after accounting for all the costs of running the company (the overheads), including those not directly related to producing products and services but before taxes, interest, etc. That includes sales and marketing costs, research and development costs, and general overhead.

Generally, a high operating margin means the business is running efficiently. However, it is essential to compare this figure to industry benchmarks – a retail business will have a very different operating margin than a manufacturing business. Also, as always, look at how the number has changed over time.

For example, suppose your operating margin decreased in one period because you made a significant investment in marketing. That might be okay if the company’s revenue figures rise in subsequent periods, especially if the costs are variable and likely to stabilize as the business achieves economies of scale. Likewise, if the company has many capital assets depreciating over time, this figure may be low for a while but increase later once the capital assets become fully depreciated.

The Bottom Line

Learning how to read a profit and loss report is valuable for anyone who must make business decisions because it empowers you with the knowledge necessary to do so confidently. However, this isn’t a skill you can develop overnight. Consider working with a full-service firm that can ensure your records are reliable and connect you with a fractional CFO to explain what they mean in simple language. Contact us today to learn how we can help.